深めて!南山GLS イベントレポート・コラム GLS教員リレーエッセイ

第3回 GLS 教員リレーエッセイ Bradley Deacon 先生

2021.08.30

"Becoming More Human Through Cultivating Intercultural Competence Development"

By Brad Deacon

For many university students in Japan, a significant part of their four-year learning journey includes study-abroad participation. Sojourning (or interacting online) via study-abroad programs affords students several valuable developmental opportunities such as building language skills, forging cross-cultural friendships, and cultivating intercultural competence.

Short-term study-abroad programs, in particular, are becoming increasingly popular in Japan (JASSO, 2019) in part to meet the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Sciences and Technology (MEXT) drive to foster "global jinzai" (global human resources) for "improving Japan's global competitiveness and enhancing the ties between nations" (MEXT, 2014). While many research efforts have focused on measuring students' language ability through study-abroad programs, fewer studies have measured their intercultural learning experiences. Given the recognition of study-abroad as a high-impact practice, finding ways to appropriately measure Japanese participants' intercultural competence (my main research area) is necessary and requires further research.

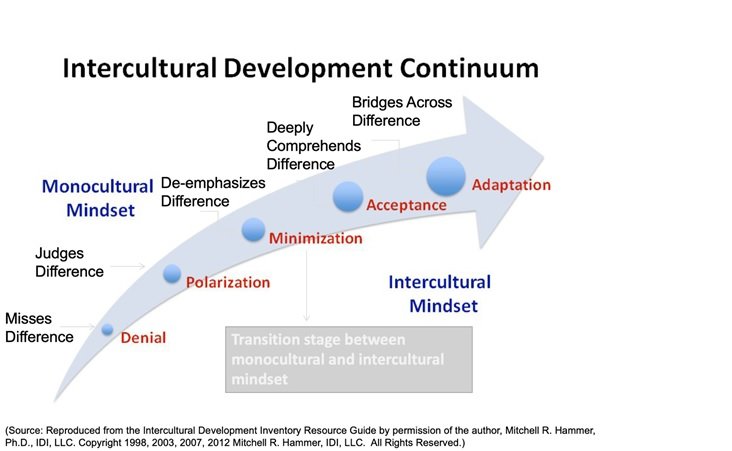

Intercultural competence has been called a key developmental area for successful cross-cultural interaction (Deardorff, 2009) and has been defined by Chen and Starosta (1998) as the "ability to effectively and appropriately execute communication behaviors that negotiate each other's cultural identity or identities in a culturally diverse environment" (p. 231). Additionally, intercultural competence has been termed an "umbrella concept" (Chen & Starosta, 2000) that encapsulates the three interrelated, and yet distinct, dimensions of intercultural awareness (cognition), intercultural sensitivity (affect), and intercultural adroitness (behavior) that are particular to cross-cultural interactants (Chen & Starosta, 1996). Research has shown that interculturally competent people can distinguish affective, behavioral, and perceptual differences between themselves and other cultural beings whilst also appreciating and respecting such differences (Chen & Starosta, 1997; 1998). Intercultural competence has gained a lot of attention in recent years as one of the key developmental areas for people to cultivate to more effectively interact with others cross-culturally. The Intercultural Development Continuum by Dr. Mitchell Hammer illustrates these developmental stages spanning ethnocentric (monocultural) to ethnorelative (intercultural) mindsets through the following model:

Understanding the relationships between cross-cultural groups is a fascinating area for me especially as a teacher-researcher abroad. In recent research, I examined the intercultural competence development of a group of Thai university students as hosts to visiting groups of Japanese students. In this study, Japanese visitor interactions provided an impetus for local Thai hosts' affective, cognitive, and behavioral intercultural competence development that partially counterbalanced their lack of local intergroup contact opportunities. This study also addressed the dominant focus on visitors in study-abroad research by investigating hosts' perspectives instead. This study was presented and published at the annual Japan Association for Language Teachers conference here:

In another recent study that is being funded with a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) No. 20K00871, I collaborated with Professor Richard Miles on a project that centered on a 6-week Arizona State University study-abroad program for Global Liberal Studies majors. To begin bridging the domestic and overseas academic divide, this exploratory study aimed to uncover the attitudinal factors impacting a group of 1st-year Japanese university students' self-perceived intercultural competence, prior to embarking on this US-based study-abroad program. The data revealed the following: 1) participants typically perceived their intercultural competence through either an individual lens and/or a collective lens (and whether they then aligned or differentiated themselves from their overall perception of Japanese intercultural competence), and 2) they adopted either a passive or proactive mindset towards their impending study-abroad experience (and whether participants exhibited specific or shallow proactive mindsets). Overall, this study suggested a need in the Japanese home context for more intentional curricular balancing of linguistic and intercultural content towards fostering intercultural attitudes that better prepare university students for studying abroad. This work was presented at the annual Cambodia TESOL conference here:

Finally, conducting research on intercultural competence provides me with a valuable opportunity to reflect on my own attitudes, behaviors, and other abilities while interacting with others abroad. Learning to more effectively interact with others cross-culturally is a humbling journey and, just like my students, I am very much a work in progress when it comes to developing my own intercultural competence. As my late father often said: "Becoming human is a lifelong journey." I have come to recognize and appreciate that taking time out to intentionally develop as an intercultural being is a necessary growth step in my life journey. In closing, I wish you all the best in your intercultural journey as well.

Bibliography

Chen, G. M., & Starosta, W. J. (1996). Intercultural communication competence: A synthesis.

Communication Yearbook, 19, 353-384.

Chen, G. M., & Starosta, W. J. (1997). A Review of the concept of intercultural sensitivity. Human Communication, 1, 1-16.

Chen, G. M., & Starosta, W. J. (1998). Foundations of intercultural communication. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Chen, G. M., & Starosta, W. J. (2000). The development and validation of the intercultural sensitivity scale. Human Communication, 3, 1-15.

Deardorff, D. K. (2009). The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Japan Student Services Organization (JASSO). (2019). Heisei 29 nendo kyotei to ni motozuku nihonjin gakusei ryugaku jokyo chosa kekka. [A 2017 survey on Japanese university students'participation in the study-abroad programs based on university-university agreements.] Retrieved from

https://www.jasso.go.jp/about/statistics/intl_student_s/2018/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2019/01/16/datah30n_1.pdf

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). (2014). Projectfor promotion of global human resource development. Retrieved from

http://www.mext.go.jp/english/highered/1326713.htm